@SS-GEN said in On this day during W.W. 2:

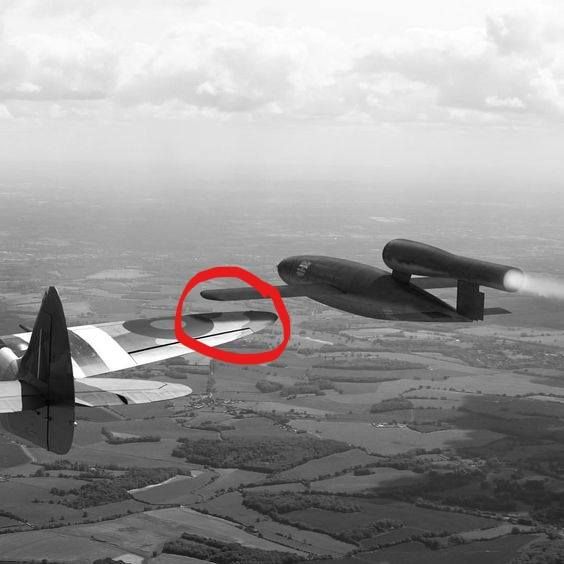

It’s funny how a missile was made to look like a plane. Needed the wings for guidance.

Just think if they had that weapon at start of war in 39. Who knows with that they would of had the jump on allies maybe for a couple of years. But that’s a but and the allies may have countered it early too just like they did in 44 45.

The reason V1 had wings (in contrast with the finned V2) wasn’t really a matter of guidance, it was a matter of how much energy it takes to move a mass of x kilograms over a distance of y kilometers (in this case, from France to London) at a speed of z kilometers per hour. The purpose of the V1’s wings, like those of a conventional aircraft, was to provide lift and thus give the V1 the ability to fly in a conventional manner on a more or less horizontal flight path. The V1, which weighed two tons, could get from point A to point B at 640 kph, on a relatively modest amount of fuel. The V2, by contrast, weighed six times more and travelled nine times faster; it followed a ballistic trajectory rather than a horizontal flight path, which is why it didn’t need wings. The trade-off, however, was a ballistic missile requires much greater thrust than an aircraft, which in turn requires larger quantities of more energetic fuel. Also note that rockets like the V2 need to carry their own fuel oxidizer, whereas air-breathing jet aircraft like the V1 don’t, which is another reason why jets can sustain themselves in flight on a relatively modest fuel load.

The question of whether the V1 and the V2 could have altered the outcome of WWII if they’d been developed, let’s say, about five years earlier is an interesting one; my impression is that, in and of themselves, they would not have done so, even if they’d been deployed in much larger quantities. The V1 and V2 were basically an expensive and inefficient alternate way (in terms of their bang-for-the-buck ratio) of bombing a city with low precision, so in that respect Germany would have been better off developing a proper heavy bomber design and a proper long-range escort fighter and producing both in large quantities. The only unquestioned advantage which the V2 had over any conventional bomber, or the V2, was that it was impossible for the defenders to intercept it once it was launched. Which brings me back to the “in and of themselves” point I mentioned earlier: the V2 by itself was not a weapon which could have changed the outcome of WWII, but if it had been equiped with an atomic warhead it would have been a serious strategic threat to the Allies. But even here, we have to be careful about jumping to conclusions. First, the German atomic program was years behind that of the US – and even the US, which devoted huge resources to the Manhattan Project, only produced (and detonated) three bombs (one was a test device) by the summer of 1945 (by which time Germany had already surrendered). So even if we were to assume (and it’s a big assumption) that Germany could have matched the Manhattan Project, and even done better by assembling its bombs a year earlier than the Americans did, the question becomes: would the Allies have surrendered if, let’s say, London and Moscow had each been nuked in mid-1944 by a V2 with a kiloton-level atomic warhead? The Russians, who’d already lost tens of millions of people and who’d seen huge areas of their countries devastated by conventional warfare, would certainly have kept going, and would probably have been even more determined than before to take their revenge against Nazi Germany. The Americans would also have kept going, with an even greater conviction than before that Nazi Germany was enormously dangerous and had to be stopped by any means possible. And my guess is that even the British would have kept going: they would have known from their intelligence sources that Germany had used up its tiny supply of warheads and they would have known that by that date the momentum of the war was on the Allied side. Furthermore, it’s hard to imagine what the practical details of a British surrender would have looked like in mid-1944, given that up until D-Day Britain was basically the operational base of a gigantic American army which, presumably, would not have meekly gone back home if Churchill – in a completely out-of-character move – would have told Eisenhower, “Thanks, but we don’t need you anymore.”