I plan on visiting Fredericksburg this year.

National Socialism being 'Right Wing'

-

@CWO:

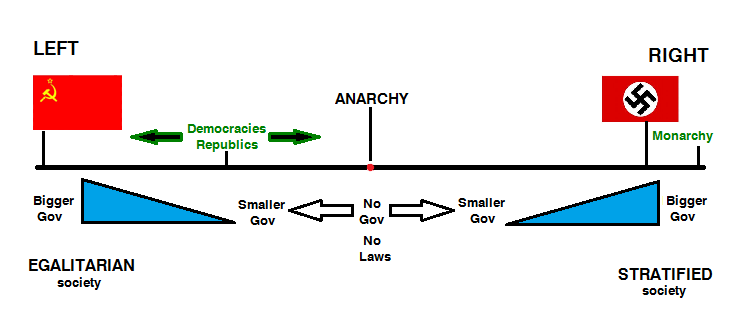

You’ve both mentioned the possible need for a two-dimensional graph, and I was thinking along the same lines. Here’s something I’ve just put together as a possible model. I’ve deliberately not positioned any political systems (or historic states) anywhere on it, but it occured to me that some of them might potentially fit in more than one place, depending on whether one is discussing pure ideology or practical politics (which gets back to one of the points LHoffman made earlier). And to pick up on something Wheatbeer mentioned, some variables wouldn’t even show up on this chart – for instance, how would one position a party that was (for example) socially progressive but fiscally conservative? I think a separate chart would be needed for those elements.

Yeah, I had been thinking about the Soviet Union (or really any Communist nation in history). Even though the communist model is based on equality of all, the proletariat, etc… in practice they have all had a very stratified society. Or at the very least divided into the political/military elites and regular citizens. Oligarchical rather than totally egalitarian.

-

Yeah, I had been thinking about the Soviet Union (or really any Communist nation in history). Even though the communist model is based on equality of all, the proletariat, etc… in practice they have all had a very stratified society. Or at the very least divided into the political/military elites and regular citizens. Oligarchical rather than totally egalitarian.

Yes, the USSR’s actual way of operating is probably what George Orwell was thinking about when he came up with the title “The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism” for the fictional book that appears in his novel 1984.

Nazi Germany had its own brand of double-speak. On the one hand, it liked to talk about the virtues of community (it sometimes arranged communal meals at which workers and industrialists all ate together) and one of its buzzwords was “Volksgenossen” (folk comrades). Politically and administratively, however, Germany became stratified along the lines of the Nazi party, with Hitler at the top and a whole hierarchy below him: gauleiters (answerable directly to Hitler) in charge of the political districts (Gau) into which the country had been divided, then kreisleiters below the gauleiters, ortsgruppenleiters below the kreisleiters, zellenleiters below the ortsgruppenleiters, and blockleiters below the zellenleiters. This political stratification didn’t directly translate into economic and social stratification, but it did parallel the oligarchical elements of Soviet society (which was also fond of the equalitarian-sounding term “comrade” – “tovarishch” in Russian) in the sense that having good Party connections could help person get ahead in life in ways that weren’t open to people who weren’t members of the Party.

-

Maybe a fruitful question would be: how did Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union differ in practice?

Off the top of my head I would contrast:

Soviet activist atheism vs Nazi ambiguous religious attitude

Soviet efforts to dissolve ethnic difference vs Nazi racism

Soviet class warfare vs Nazi class management -

(I pose that question because I think that the difference is not at all analogous to Bloods/Crips as the OP suggested)

-

Maybe a fruitful question would be: how did Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union differ in practice?

Off the top of my head I would contrast:

Soviet activist atheism vs Nazi ambiguous religious attitude

Soviet efforts to dissolve ethnic difference vs Nazi racism

Soviet class warfare vs Nazi class managementGood points, but I do think that one of the most important defining elements of each was internationalism vs nationalism. Someone else mentioned this earlier, not sure if it was you Wheatbeer, but it does sort of go along with the dissolve ethnicity vs racism point. National Socialism was less about world-conquering than Soviet Communism. Was it Lenin/Marx who espoused the world (international) communism model? But then Stalin who modified it to “Socialism in one country”? I forget exactly, but I remember reading the technicality that “communism” was intrinsically a world-wide system and the word should only be applied as such. Whereas “socialism” was the government of an individual nation. Therefore all the socialist countries would make up the whole of world communism. Something like that. Either that or Stalin saw the need to establish socialism in the Soviet Union and expand it worldwide from there. I think that sounds more accurate. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socialism_in_One_Country)

Anyway, the goal of communism being international vs national socialism being intrinsically national. Russia and China and France and Brazil could all become communist (of equal standing with all the other communists), but national socialism preserved all nation-state distinctions and prerogatives in any practicing country. A National Socialist Italy would be similar to but different from a National Socialist Germany. A communist China theoretically would have equal political footing (and alliance) with Soviet Russia. However, with the socialism in one country practice, it was the USSR that pulled all the strings of her satellites.

National Socialism in Germany was all about Germans. National Socialism in France (had it existed) would have been all about the French. National Socialism in Australia would have been all about Australians. Ethnicity may play a part, but primarily National Socialism (Fascism) would focus on a country’s population and their citizenship. Communism would theoretically care only about party affiliation and not about ethnicity or citizenship.

-

Maybe a fruitful question would be: how did Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union differ in practice?

The first difference that comes to mind has to do with their economic systems, both in theory and in practice. The USSR’s economic philosophy was, at least in terms of its general lines, Marxist (at least to my knowledge, since economics – Marxist or otherwise – isn’t my strong suit). Philosphically, Marxism was an anathema to the Nazis. To give just one example: soon after he came to power, Hitler granted German workers the May Day holiday they had demanded…then abolished the labour unions the following day.

In practice, the USSR under Stalin featured collectivized farms, state-owned industries, centralized economic planning (the notorious Five-Year Plans being an example) and, as far as I know, very little private-sector activity (at least officially). Nazi Germany’s economy, especially during WWII, was a complicated mixture of private enterprise and state control which has been described as “falling between the barstools” of the USSR’s centralized economy and the USA’s system of free-market capitalism. To my knowledge, the big industrial companies like Krupp remained in private hands, but their businesses were heavily involved in manufacturing things for the government and the Wehrmach, with government and/or military representatives dictating specifications to them (sometimes in the course of acrimonious arguments).

-

LHoffman,

Certainly that works as a contrast since the Soviets did foment revolution in their own mold.CWOMarc,

I was hinting at that by mentioning class dynamics, but I wasn’t sure how and to what extent the Nazi state altered base economic organization. Clearly, they didn’t come anywhere near the Soviets in terms of radical economic reorganization (Soviet agriculture was particularly shocking). -

I wasn’t sure how and to what extent the Nazi state altered base economic organization.

One major economic change that occurred in Germany as the war progressed was an increasing reliance on foreign workers. These ranged from people who had “volunteered” to various degrees (for instance in exchange for the repatriation of prisoners of war) to conscripts and deportees (see Vichy France’s STO, the Service de Travail Obligatoire) to outright slave labour (as in the notorious Mittelwerk complex). These were employed to fill the gap caused by the absorption of German men into the armed forces, and by the Nazi regime’s initial reluctance to bring German women into the industrial workforce. The result, ironically, was that Berlin (and other big urban areas) became precisely what Hitler had hated so much about Vienna as a young man: a city full of foreigners.

-

@CWO:

You’ve both mentioned the possible need for a two-dimensional graph, and I was thinking along the same lines. Here’s something I’ve just put together as a possible model. I’ve deliberately not positioned any political systems (or historic states) anywhere on it, but it occured to me that some of them might potentially fit in more than one place, depending on whether one is discussing pure ideology or practical politics (which gets back to one of the points LHoffman made earlier). And to pick up on something Wheatbeer mentioned, some variables wouldn’t even show up on this chart – for instance, how would one position a party that was (for example) socially progressive but fiscally conservative? I think a separate chart would be needed for those elements.

Yeah, I had been thinking about the Soviet Union (or really any Communist nation in history). Even though the communist model is based on equality of all, the proletariat, etc… in practice they have all had a very stratified society. Or at the very least divided into the political/military elites and regular citizens. Oligarchical rather than totally egalitarian.

Ideology and reality are 2 different things. A particular ideology might want certain circumstances but reality pushes it in a different direction. For example, the Leninists hoped for a more libertarian society–but it didn’t happen that way, given the pressures of war, the inheritance of the traditions of the Russian state (known for brutality, secret police, contempt for human rights, and the like), and the Leninists’ contempt for Western liberal standards.

Similarly, many national socialists in Germany would have liked far more radical changes in economic organization and religious life but it was impossible given the demands of war and the need to placate the masses as well as the industrialists.

Many theorists of the 40s-50s argued there was a worldwide trend toward buerocratic collectivism. I think the Cold War actually intensified this trend–both powers gravitated towards stratified buerocratic oligarchy as they competed with one another.

One more point to keep in mind is that the Stalinist turn in the Soviet Union was not percieved as a “leftist” move–on the contrary, Lenin characterized his ideological opponents in Western Europe as “infantile leftists”, and Stalin himself was not considered a leftist or an internationalist, although he did end up adopting many Trotskyist policies after he expelled Trotsky, and Stalin was a materialist theoretically.

Left/right may be somewhat useful when talking about dreams and/or ideology, as long as one clearly defines what one means by left and right, but it is probably useless when talking about reality.

One last point–I can’t commend any left/right spectrum that places anarchists on the right. Anarchists tend to argue against ownership of land or means of production, and tend to argue that meaningful liberty requires meaningful equality. And they are anti-authoritarian and anti-hierarchy. These are traditionally leftist notions. It is interesting how the anarcho-capitalists have taken up the Old Left idea of anti-statism and made it theirs. The irony is that the socialists in the 19th century (including even Marx) shared this dream of doing away with the state. The turn towards left ‘statism’ seems to have occurred largely after 1900 and the emergence of ‘progressive’ political parties that entered parliament and implemented many socialist ideas on a national level.

-

The thing to keep in mind is that ideology and reality are 2 different things. Â A particular ideology might want certain circumstances but reality pushes it in a different direction. […] Left/right may be somewhat useful when talking about dreams and/or ideology, as long as one clearly defines what one means by left and right, but it is probably useless when talking about reality.

This reminds me of the old joke about a new invention being demonstrated before a committee, whose members are all impressed by its performance except for one person who asks the inventor, “It obviously works in practice, but does it work in theory?” :lol:

-

Many theorists of the 40s-50s argued there was a worldwide trend toward buerocratic collectivism. I think the Cold War actually intensified this trend–both powers gravitated towards stratified buerocratic oligarchy as they competed with one another.

Interesting thought. More than a grain of truth perhaps.

One last point–I can’t commend any left/right spectrum that places anarchists on the right. Anarchists tend to argue against ownership of land or means of production, and tend to argue that meaningful liberty requires meaningful equality. And they are anti-authoritarian and anti-hierarchy. These are traditionally leftist notions. It is interesting how the anarcho-capitalists have taken up the Old Left idea of anti-statism and made it theirs. The irony is that the socialists in the 19th century (including even Marx) shared this dream of doing away with the state. The turn towards left ‘statism’ seems to have occurred largely after 1900 and the emergence of ‘progressive’ political parties that entered parliament and implemented many socialist ideas on a national level.

If we are just talking about anarchy as it refers to the level of government then, respectfully, yes, anarchists should be at one end (usually called Right) and totalitarian or ultimate government societies should be at the other (usually called Left). That was the point of the Ideological graph, which perhaps is not the right term for it. I agree that anarchists and communists espouse many of the same tenets. However, the ideal of communism must intrinsically be maintained by a surpassing government… or am I wrong? I have not read Das Kapital. Political anarchists, while espousing similar ideals, goes about it in the complete opposite fashion: lack of government. I assume that for the anarchists non-governmental utopia to be maintained everyone must work together with no malice and complete understanding. Talk about a disconnect from reality.

Besides which, it seems like political anarchists are quite different from the literal definition of anarchy (which is what is meant on the spectrums I have included). Just from Google, Anarchy = a state of disorder due to absence or nonrecognition of authority or absence of government and absolute freedom of the individual, regarded as a political ideal. Even if we consider the second portion, it still references absence of government. Did Marx (and Lenin) intend for communism to have no government? If so, they were just advocating an anarchy pipe-dream in which there was no materialism, no personal ownership and fully egalitarian. This would be contravened immediately just because anarchy means people can do what they want without any sort of higher level enforcement.

-

Capitalism as we know it is very young relative to the age of our species.

I don’t think it’s irrational to believe that some day, humans might transition to something different without the prerequisite of a repressive government apparatus.

-

Capitalism as we know it is very young relative to the age of our species.

I don’t think it’s irrational to believe that some day, humans might transition to something different without the prerequisite of a repressive government apparatus.

Isn’t that sort of what dialectical materialism says about the inevitable progress of human societies towards a more perfect state, or something along those lines? (Philosophy is even less my area than economics, so I’m really out of my depth here.)

-

I don’t predict any particular outcome and I don’t believe that future developments will necessarily improve the human condition.

But I embrace the general concept that material change (notably, technology) will ultimately generate social change.

-

Many theorists of the 40s-50s argued there was a worldwide trend toward buerocratic collectivism. I think the Cold War actually intensified this trend–both powers gravitated towards stratified buerocratic oligarchy as they competed with one another.

Interesting thought. More than a grain of truth perhaps.

One last point–I can’t commend any left/right spectrum that places anarchists on the right. Anarchists tend to argue against ownership of land or means of production, and tend to argue that meaningful liberty requires meaningful equality. And they are anti-authoritarian and anti-hierarchy. These are traditionally leftist notions. It is interesting how the anarcho-capitalists have taken up the Old Left idea of anti-statism and made it theirs. The irony is that the socialists in the 19th century (including even Marx) shared this dream of doing away with the state. The turn towards left ‘statism’ seems to have occurred largely after 1900 and the emergence of ‘progressive’ political parties that entered parliament and implemented many socialist ideas on a national level.

If we are just talking about anarchy as it refers to the level of government then, respectfully, yes, anarchists should be at one end (usually called Right) and totalitarian or ultimate government societies should be at the other (usually called Left). That was the point of the Ideological graph, which perhaps is not the right term for it. I agree that anarchists and communists espouse many of the same tenets. However, the ideal of communism must intrinsically be maintained by a surpassing government… or am I wrong? I have not read Das Kapital. Political anarchists, while espousing similar ideals, goes about it in the complete opposite fashion: lack of government. I assume that for the anarchists non-governmental utopia to be maintained everyone must work together with no malice and complete understanding. Talk about a disconnect from reality.

Did Marx (and Lenin) intend for communism to have no government? If so, they were just advocating an anarchy pipe-dream in which there was no materialism, no personal ownership and fully egalitarian. This would be contravened immediately just because anarchy means people can do what they want without any sort of higher level enforcement.

This Faq is a pretty good introduction to what (classical) anarchism is all about.

http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/index.html

In general, both communists and anarchists want a stateless communist society where there is widespread equality and liberty. The big disagreement is over how to bring this about. See for example Benjamin Tucker for the individualist anarchist take on it.

http://praxeology.net/BT-SSA.htmMarx believed that a dictatorship of the proletariat (eg, a government, similar to Jacobin France or the Paris Comune) would be necessary as a transitional phase to socialism/communism. According to Marx, once the means of production was in the hands of local communities instead of capitalists (or kings, or the church), government would eventually wither away. According to Marx, government is essentially the domination of one class over another. So for Marx, ‘communism’ describes a stateless society with common or collective ownership of land and the means of production. ‘Socialism’ or the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ is the transition from captialism to communism under the leadership of a communist party apparatus (eg, where the proletarian class is dominant over the capitalist class).

Marx’s view is distinct from the anarchist tradition, which 1) rejected electoralism and parliamentarism and 2) wanted a direct transition to federalist rule by local unions and community councils 3) is more radical and idealist than the more pragmatic Marxist tradition. A good illustration of the conflict between socialists and anarchists is the Spanish Revolution. Revolutionary Catalonia had alot of the features of the society classical anarchism was aiming at.

-

Anyway, as far as left-right spectrums go, if you want to define right as less government and left as more-government, then I suppose it’s fair enough to put anarchism on the right. The basic problem is that the above way of defining left/right seems ahistorical (given that originally, the ‘right’ was associated with hierarchy, authority, traditional government etc) and thus introduces more confusion than clarity.

-

Anyway, as far as left-right spectrums go, if you want to define right as less government and left as more-government, then I suppose it’s fair enough to put anarchism on the right. The basic problem is that the above way of defining left/right seems ahistorical (given that originally, the ‘right’ was associated with hierarchy, authority, traditional government etc) and thus introduces more confusion than clarity.

Understood, and I do agree. Which, again, is why I tried to come up with some combination of the two which tries to reconcile the differences:

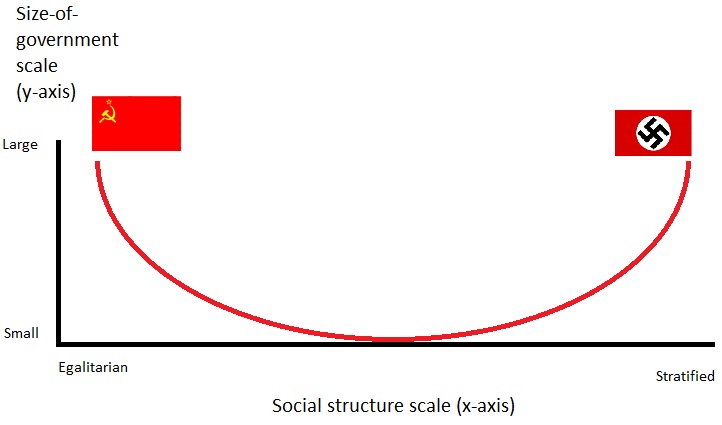

This is imperfect, but better than a simple L-R scale.

-

This is imperfect, but better than a simple L-R scale.

The two blue triangles at the bottom of your chart are making me wonder if perhaps an inverted bell curve would be a good way of describing the continuum – something like this for example:

-

Anyway, as far as left-right spectrums go, if you want to define right as less government and left as more-government, then I suppose it’s fair enough to put anarchism on the right.Â

And just to follow up on that point: on the new chart I’ve just posted, anarchism would be at the bottom of the chart rather than on the left or the right, with a value of y=0. The top of the chart could be given a value of, let’s say, y=100, with the USSR and Nazi Germany both sharing the same high y-axis score. If anarchism (basically, the absence of government) is the term corresponding to value of y=0, I imagine that the opposite concept (the omnipresence and omnipotence of government) could be labeled totalitarianism and that it would apply to all scores of y=100, regardless of where they fit on the x-axis.

-

@CWO:

Anyway, as far as left-right spectrums go, if you want to define right as less government and left as more-government, then I suppose it’s fair enough to put anarchism on the right.�

And just to follow up on that point: on the new chart I’ve just posted, anarchism would be at the bottom of the chart rather than on the left or the right, with a value of y=0. The top of the chart could be given a value of, let’s say, y=100, with the USSR and Nazi Germany both sharing the same high y-axis score. If anarchism (basically, the absence of government) is the term corresponding to value of y=0, I imagine that the opposite concept (the omnipresence and omnipotence of government) could be labeled totalitarianism and that it would apply to all scores of y=100, regardless of where they fit on the x-axis.

Yes, I do very much like this interpretation. While searching for similar scales and images, I found a 3-D representation that used a funnel as a model. The Totalitarian government structure was at some point near the edge of the circle on the top and anarchy was at the bottom of the funnel portion in the middle. Anyway, that reminded me of your curve.