@aequitas:

Something??

And you say that you don’t deny the Holocaust??To underline your arguments you should have evidence of it.

You don’t! So just leave it!!

First you blame the Western Allies for the imaginary Food Blockade, now you are saying it was the beasty Pluto-rusky-soviets??It is just sad… :-(

And you say that you don’t deny the Holocaust??

Correct. I do not deny the Holocaust.

To underline your arguments you should have evidence of it.

If there are specific factual claims I’ve made for which you’d like to see more evidence, just ask. My typical response to such requests is to provide evidence of my assertions. In supporting such claims, I have never cited pro-Nazi or other far right sources. My rationale is that a far right source could be expected to present the Nazis’ case in the most favorable light, and might even be willing to exaggerate things in the Nazis’ favor. If on the other hand a mainstream (anti-Nazi) source is willing to admit the truth of something which casts a less than 100% favorable light on the Allies’ actions, then that admission is most likely true.

First you blame the Western Allies for the imaginary Food Blockade

After his political career ended, former U.S. president Herbert Hoover wrote a series of books. One of those books was Freedom Betrayed. On page 589 of Freedom Betrayed, Hoover wrote the following:

[In 1939] the Polish Government escaped to London under Prime Minister Wladyslaw Sikorski. He requested me to organize relief for his country. My old colleagues and I did so, but after about one year, during which about $6,000,000 was raised and supplies had been shipped, our work was stopped by the British blockade.

Neville Chamberlain had of course blockaded metals, oil, weapons, ammunition, and other items you’d normally expect to be blockaded. Churchill added food to the list of contraband items. That is why Hoover was able to send food to the starving Poles during the first year of the war, and was unable to send food to them thereafter.

The Wikipedia article expands on the subject of this blockade.

As 1940 drew to a close, the situation for many of Europe’s 525 million people was dire. With the food supply reduced by 15% by the blockade and another 15% by poor harvests, starvation and diseases such as influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis, typhus and cholera were a threat. Germany was forced to send 40 freight cars of emergency supplies into occupied Belgium and France, and American charities such as the Red Cross, the Aldrich Committee, and the American Friends Service Committee began gathering funds to send aid. Former president Herbert Hoover, who had done much to alleviate the hunger of European children during World War I, wrote:[63]

The food situation in the present war is already more desperate than at the same stage in the [First] World War. … If this war is long continued, there is but one implacable end… the greatest famine in history.

Adam Tooze’s book Wages of Destruction has been praised by The Times (London), The Sunday Times (London), The Wall Street Journal, and History Today. The Financial Times called it “masterful.” On pages 418 - 419 Tooze writes the following:

After 1939 the supply of food in Western Europe was no less constrained than the supply of coal. . . . Grain imports in the late 1930s had run at the rate of more than 7 million tons per annum mostly from Argentina and Canada. These sources of supply were closed off by the British blockade. . . . By the summer of 1940, Germany was facing a Europe-wide agricultural crisis. . . . By 1941 there were already signs of mounting discontent due to the inadequate food supply. In Belgium and France, the official ration allocated to ‘normal consumers’ of as little as 1,300 calories per day, was an open invitation to resort to the black market.

now you are saying it was the beasty Pluto-rusky-soviets

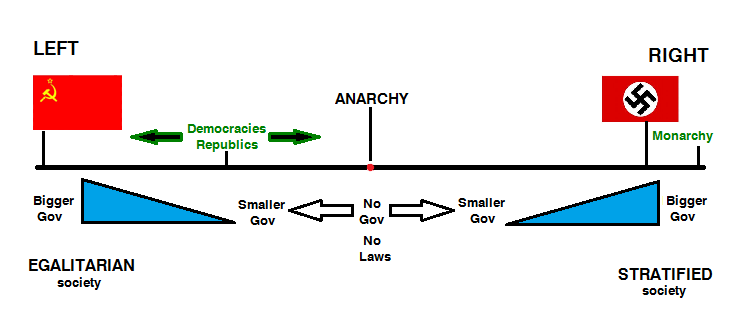

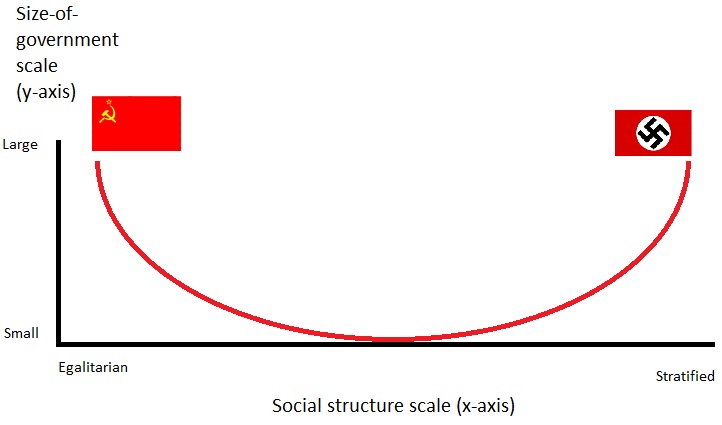

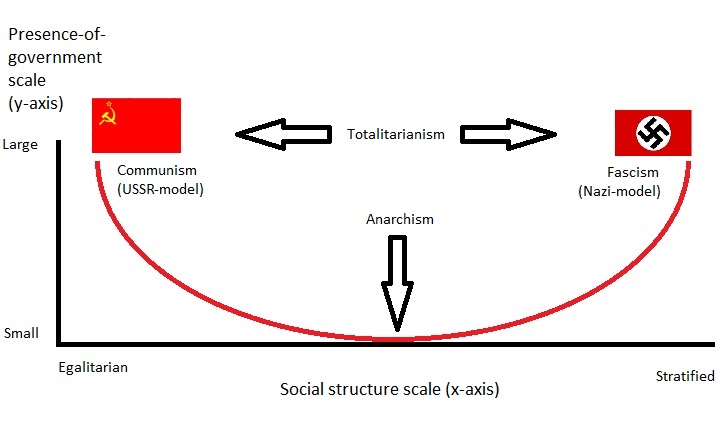

The food blockade was of course imposed by the Western Allies. Those nations are typically known as democracies, even though a study showed that, in practice, decisions are made on a plutocratic basis. Princeton University found there is zero correlation between what the bottom economic 90% wants and what the federal government actually does. (The data go back a number of decades, but do not go all the way back to WWII. The study therefore represents very strong evidence, but not proof, that the U.S. had been a plutocracy during WWII.)

I regard most politicians as shills for America’s plutocrat class. The brutality of the Allied food blockade was not reflective of a murderous American population. It was reflective of a murderous, evil plutocrat class.