Saints and Soldiers is really good equipment-wise, the movie itself is mediocre. It’s on Amazon prime instant video. It’s set in the opening days of the battle of the bulge. The only thing I noticed is that the Germans who shoot 70-plus American POW’s at Malmedy are regular Wehrmacht and not SS, but whatever.

WW2 Article: Advanced German Technology

-

CWO Marc,

Actually, guidance systems were in existence during WWII:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Beams

Guidance beams were used for the V-2 though the system was not foolproof:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V-2

Accuracy increased over the course of the war, particularly on batteries where Leitstrahl-Guide Beam apparatus was installed.

British intelligence leaked falsified information implying that the rockets were over-shooting their London target by 10 to 20 miles. This tactic worked and for the remainder of the war most landed in Kent due to erroneous recalibration.

Had the war extended to 1947, I think it is possible that the guidance systems would have improved to a significant accuracy (unless of course the counter-measures also improved). A moving ship, I doubt could have been hit unless it (or a very near submarine) were transmitting a signal, but certainly a city and probably even a city block could have been targeted. And, of course, chemical, biological, and especially atomic weapons would not have needed great accuracy as KurtGodel7 stated.

I think the reason that today the US Navy isn’t overly worried about Chinese missiles sinking one of its carriers is that they have some very potent countermeasures…

KurtGodel7;

While reading the article on the V-2, I came across this interesting bit of information:

The V-2 program was the single most expensive development project of the Third Reich:[citation needed] 6,048 were built, at a cost of approximately 100,000 Reichsmarks each; 3,225 were launched. SS General Hans Kammler, who as an engineer had constructed several concentration camps including Auschwitz, had a reputation for brutality and had originated the idea of using concentration camp prisoners as slave laborers in the rocket program. The V-2 is perhaps the only weapon system to have caused more deaths by its production than its deployment.[39]

The V-2 consumed a third of Germany’s fuel alcohol production and major portions of other critical technologies:[41] to distil the fuel alcohol for one V-2 launch required 30 tons of potatoes at a time when food was becoming scarce.[42] Due to a lack of explosives, concrete was used and sometimes the warhead contained photographic propaganda of German citizens who had died in allied bombing.[18]

I find the embedded quote particularly an interesting point of view:

“… those of us who were seriously engaged in the war were very grateful to Wernher von Braun. We knew that each V-2 cost as much to produce as a high-performance fighter airplane. We knew that German forces on the fighting fronts were in desperate need of airplanes, and that the V-2 rockets were doing us no military damage. From our point of view, the V-2 program was almost as good as if Hitler had adopted a policy of unilateral disarmament.” (Freeman Dyson)[40]

Perhaps this (and the lack of support given to Goddard by the Americans who certainly could have afforded it) is an indication of better operational research on the part of the allies. Why spend the money on a rocket inflicting minimal damage to the enemy when the same development money could help fund the manhattan project and the construction money buy a useful fighter instead?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operational_research#Second_World_War

which might be one of the advantages the allies had during the war, though I am not certain it should be called a technological advantage.

I have heard it stated that the V-2 program cost the same as the manhattan project, which relates directly to the question of operational research. But I can’t find a good source for this, the best approximation I have is the following: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichsmark

The Reichsmark was put on the gold standard at the rate previously used by the Goldmark, with the U.S. dollar worth 4.2 ℛℳ.

; therefore 100,000RM * 6000 /4.2 = $142M in 1938 dollars…probably not a great method to compare the costs…maybe someone knows (or can find) a better comparison?

I am really enjoying this discussion, thanks to everyone who is participating!

-

@221B:

CWO Marc,

Actually, guidance systems were in existence during WWII:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Beams

Guidance beams were used for the V-2 though the system was not foolproof:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V-2

Accuracy increased over the course of the war, particularly on batteries where Leitstrahl-Guide Beam apparatus was installed.

British intelligence leaked falsified information implying that the rockets were over-shooting their London target by 10 to 20 miles. This tactic worked and for the remainder of the war most landed in Kent due to erroneous recalibration.

Had the war extended to 1947, I think it is possible that the guidance systems would have improved to a significant accuracy (unless of course the counter-measures also improved). A moving ship, I doubt could have been hit unless it (or a very near submarine) were transmitting a signal, but certainly a city and probably even a city block could have been targeted. And, of course, chemical, biological, and especially atomic weapons would not have needed great accuracy as KurtGodel7 stated.

I think the reason that today the US Navy isn’t overly worried about Chinese missiles sinking one of its carriers is that they have some very potent countermeasures…

KurtGodel7;

While reading the article on the V-2, I came across this interesting bit of information:

The V-2 program was the single most expensive development project of the Third Reich:[citation needed] 6,048 were built, at a cost of approximately 100,000 Reichsmarks each; 3,225 were launched. SS General Hans Kammler, who as an engineer had constructed several concentration camps including Auschwitz, had a reputation for brutality and had originated the idea of using concentration camp prisoners as slave laborers in the rocket program. The V-2 is perhaps the only weapon system to have caused more deaths by its production than its deployment.[39]

The V-2 consumed a third of Germany’s fuel alcohol production and major portions of other critical technologies:[41] to distil the fuel alcohol for one V-2 launch required 30 tons of potatoes at a time when food was becoming scarce.[42] Due to a lack of explosives, concrete was used and sometimes the warhead contained photographic propaganda of German citizens who had died in allied bombing.[18]

I find the embedded quote particularly an interesting point of view:

“… those of us who were seriously engaged in the war were very grateful to Wernher von Braun. We knew that each V-2 cost as much to produce as a high-performance fighter airplane. We knew that German forces on the fighting fronts were in desperate need of airplanes, and that the V-2 rockets were doing us no military damage. From our point of view, the V-2 program was almost as good as if Hitler had adopted a policy of unilateral disarmament.” (Freeman Dyson)[40]

Perhaps this (and the lack of support given to Goddard by the Americans who certainly could have afforded it) is an indication of better operational research on the part of the allies. Why spend the money on a rocket inflicting minimal damage to the enemy when the same development money could help fund the manhattan project and the construction money buy a useful fighter instead?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operational_research#Second_World_War

which might be one of the advantages the allies had during the war, though I am not certain it should be called a technological advantage.

I have heard it stated that the V-2 program cost the same as the manhattan project, which relates directly to the question of operational research. But I can’t find a good source for this, the best approximation I have is the following: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichsmark

The Reichsmark was put on the gold standard at the rate previously used by the Goldmark, with the U.S. dollar worth 4.2 ℛℳ.

; therefore 100,000RM * 6000 /4.2 = $142M in 1938 dollars…probably not a great method to compare the costs…maybe someone knows (or can find) a better comparison?

I am really enjoying this discussion, thanks to everyone who is participating!

Thanks for the good post! It looks like I have some reading to do about the guidance systems the V2s could potentially have used! If they could eventually have become reasonably accurate weapons, then Hitler’s decision to mass produce them seems somewhat less questionable. He may have reasoned that by 1946 or '47 the V2 would become a weapon with actual military value. Once that happened, he’d want to have them in full production. If such indeed was his reasoning, he may have felt that putting them into production a couple years too early would serve two purposes. 1) It would force the Germans to learn how to produce large numbers of V2s quickly, so that they’d be ready to massively deploy the more accurate V2s once they were available. 2) The V2s would distract Allied bombers. One could argue that, had that industrial effort gone into producing fighter aircraft instead, Germany would have lacked the fuel to use all those extra fighters.

As for the cost of the V2 program–my impression is that whatever industrial effort was expended mass producing V2s was almost completely wasted. But the effort invested into research about how to build better rockets should be placed into a different category.

Toward the end of the war, Germany had developed some extremely effective air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles. I don’t know how much overlap there was between the rocketry research for those things and the V2 research effort. But often a research application which seems specific to one area can have an application in another. Germany and the U.S. should have provided solid funding for rocket research–which was, after all, the origin of the ICBM–but neither nation should have mass produced V2-like weapons.

-

@221B:

Actually, guidance systems were in existence during WWII:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_BeamsIn existence, yes, but with nowhere near the kind of accuracy needed to hit a specific building. The British GEE system, for instance, allowed bombers to hit their targets with an accuracy of 165 yards at short ranges, of a mile at longer ranges over Germany, and of two miles at its extreme range of 400 miles (640 km). And it was designed to guide bombers, not ballistic missiles.

-

As for the cost of the V2 program–my impression is that whatever industrial effort was expended mass producing V2s was almost completely wasted. But the effort invested into research about how to build better rockets should be placed into a different category.

Research can pay all sorts of unexpected dividends, so it does have value. That said, however, it can be argued that Germany’s multiple research programs into all kinds of advanced technologies suffered from the “trying to herd cats” syndrome. It scattered its limited resources on a plethora of projects, including some of debatable practical value, rather than identifying a few that had the most potential to win the war and concentrating all its marbles in those areas. And it didn’t just do this in the high-tech weapons field. Just as an example, it developed too many tank types – including the Maus, which was too slow to have much practical value, and too big and heavy to handle bridges or to transport on most railroads. The Soviets, by contrast, focused on manufacturing just a few basic but effective tank types designed for easy mass production, and as their technology got better they used these improvements mainly to producing upgraded models (as in the switch from the T-34/76 to the T-34/85) rather than developing new machines.

There’s also the larger point that it’s probably not a good idea to become mesmerized by the theoretical potential of high-tech “wonder weapons” at the expense of using a nation’s economic and industrial resources as efficiently as possible to produce the basic weapons and other tools needed in wartime, or having a coherent strategic plan for fighting and winning the war. One of John Keegan’s books (I think it’s The Mask of Command) argues that Hitler in many ways never progressed beyond the level of a corporal (which he was in WWI) in his strategic thinking. Keegan describes Hitler bending over a map of Stalingrad, expressing satisfaction over the news that this particular platoon had captured that particular block, while his generals stood nearby rolling their eyes and wondering what on earth any of this had to do with the overall situation on the Eastern Front. As the situation deteriorated more and more in 1944 and 1945, Hitler seems to have clung increasingly to the idea that the “Wunderwaffen” under development would save the day for Germany at the last moment, and compensate for the errors which Germany had made up to that point.

I think I once mentioned it somewhere else on the board, but Arthur C. Clarke’s short story “Superiority” – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superiority_(short_story) – explores the question of whether it’s better to have a vast number of ordinary weapons or a small number of super-weapons. Clarke wrote in one of his book introductions that the story had been directly inspired by WWII.

-

@CWO:

As for the cost of the V2 program–my impression is that whatever industrial effort was expended mass producing V2s was almost completely wasted. But the effort invested into research about how to build better rockets should be placed into a different category.

Research can pay all sorts of unexpected dividends, so it does have value. That said, however, it can be argued that Germany’s multiple research programs into all kinds of advanced technologies suffered from the “trying to herd cats” syndrome. It scattered its limited resources on a plethora of projects, including some of debatable practical value, rather than identifying a few that had the most potential to win the war and concentrating all its marbles in those areas. And it didn’t just do this in the high-tech weapons field. Just as an example, it developed too many tank types – including the Maus, which was too slow to have much practical value, and too big and heavy to handle bridges or to transport on most railroads. The Soviets, by contrast, focused on manufacturing just a few basic but effective tank types designed for easy mass production, and as their technology got better they used these improvements mainly to producing upgraded models (as in the switch from the T-34/76 to the T-34/85) rather than developing new machines.

There’s also the larger point that it’s probably not a good idea to become mesmerized by the theoretical potential of high-tech “wonder weapons” at the expense of using a nation’s economic and industrial resources as efficiently as possible to produce the basic weapons and other tools needed in wartime, or having a coherent strategic plan for fighting and winning the war. One of John Keegan’s books (I think it’s The Mask of Command) argues that Hitler in many ways never progressed beyond the level of a corporal (which he was in WWI) in his strategic thinking. Keegan describes Hitler bending over a map of Stalingrad, expressing satisfaction over the news that this particular platoon had captured that particular block, while his generals stood nearby rolling their eyes and wondering what on earth any of this had to do with the overall situation on the Eastern Front. As the situation deteriorated more and more in 1944 and 1945, Hitler seems to have clung increasingly to the idea that the “Wunderwaffen” under development would save the day for Germany at the last moment, and compensate for the errors which Germany had made up to that point.

I think I once mentioned it somewhere else on the board, but Arthur C. Clarke’s short story “Superiority” – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superiority_(short_story) – explores the question of whether it’s better to have a vast number of ordinary weapons or a small number of super-weapons. Clarke wrote in one of his book introductions that the story had been directly inspired by WWII.

You make a lot of good points, and I agree with about 90% of what you’ve written. (Without having a definitive opinion, one way or the other, about the remaining 10%.)

I fully agree that Germany should have had fewer weapons designs, and should have concentrated its engineering and development efforts into improving those weapons. Its failure to do so was a major reason why the Soviet Union produced between 3 - 4 times as many land weapons in 1942 as did Germany, and nearly twice as many military aircraft in ‘42. (This, despite many of the Soviets’ factories had been overrun or relocated during '41.)

It’s harder to say that their research effort should have been concentrated into a few key areas. In hindsight, it’s easy to see which projects could have brought immediate military benefit, which ones would have been associated with more delayed gratification, and which were merely dead ends. (Though as you hinted at, a project which yields no direct military benefit may still significantly contribute to some other, more useful project.)

Toward the end of the war, Germany had developed the assault rifle, long range Panzerfaust anti-tank weapons, Me 262 jets which attained a 5:1 kill ratio (10:1 when fitted with the latest air-to-air missiles), and advanced type XXI submarines which would have been very difficult for the Allies to detect or sink. These were exactly the kinds of weapons Germany needed to win the war. However, these weapons appeared too late, and in too small quantities, to affect the war’s outcome.

One problem Germany faced is that its entire war effort had been more or less thrown together in a hurry. In 1933 when Hitler came to power, Germany’s army was a token force with no tanks. Germany as a whole was not allowed to build powered aircraft of any kind. A situation in which the military has few or no weapons means that factories will not be geared up for military production. Given that Germany was in the midst of a depression, and that the major democracies had closed themselves to German exports, German factories were not very well geared up for any kind of production! Going from a situation like that (in 1933) to war with Britain and France (1939) was just too small a time for them to get everything right. The emphasis during those years was on getting new military production running quickly, not necessarily on the disciplined standardization of a few designs which you described, and which was clearly necessary.

Toward the end of the war, the Germans had become fully aware of the problems you described, and were working to correct them. The E-Series tanks would have had far fewer moving parts, would have been easier to build and maintain, and would have represented far fewer tank designs, than Germany’s previous tank designs. The E-25 would have replaced the Panzer III and Panzer IV, the E-50 was to replace the Tiger I and the Panther, and the E-75 was to replace the Tiger II. Plans were also underway to improve the turrets of the Panthers and, therefore, of the subsequent E-50s and E-75s. The armor of the turrets was to be thicker–three times thicker on the roof–but the turrets would be lighter due to a narrower design.

Had they had another year or two, the German research and engineering effort would have resulted in tanks that were not only qualitatively superior to anything the Allies had, but which would have been easy to mass produce and maintain. Not only that, the Germans had by far the best handheld anti-tank weapons of the war. The Panzerfaust 150 could penetrate over 200 mm of armor at a range of 150 meters. The bazooka was significantly inferior, and was more useful against pillboxes and so forth than it was against German tanks. With the best tank design, the best aircraft designs, the best infantry weapons, by far the best submarine designs, and a number of other useful designs and innovations, Germany’s research and development effort seems quite impressive! That said, you are correct to say the way it was organized could and should have been better. I especially agree with your assertion that an engineering and production effort should begin with someone at the top having a clear vision of how he intends to achieve victory, who then selects the weapon designs necessary to put that vision into effect.

I’ve read the short story you mentioned, and it’s overly critical of the German quest for super weapons. Had Germany used exactly the same weapon designs as its enemies, and no other weapon designs, the outcome of the war would have been about the same. Germany’s enemies simply had too much production capacity and too much manpower for Germany to hope for victory. Only a decisive advantage in quality could allow Germany to balance out the Allies’ overwhelming advantage in quantity.

For most of the war, Germany produced weapons of standard-issue quality, albeit in smaller quantities than should have been the case. Those small quantities were because of various problems you identified (too many designs in production, too many moving parts per weapon, etc.), and not because of Germany’s efforts to obtain super weapons such as jets or air-to-air missiles. Developing the super weapons for the mid- and long-term made sense; and in fact the jet could probably have been finished noticeably sooner had it received a higher research and development priority. But in the meantime, Germany should have been more Soviet Union-like in its production of normal quality weapons. By that I mean it should have focused on a small number of designs, and those designs should have been as simple and as easily mass produced as possible.

-

For most of the war, Germany produced weapons of standard-issue quality, albeit in smaller quantities than should have been the case. Those small quantities were because of various problems you identified (too many designs in production, too many moving parts per weapon, etc.), and not because of Germany’s efforts to obtain super weapons such as jets or air-to-air missiles. Developing the super weapons for the mid- and long-term made sense; and in fact the jet could probably have been finished noticeably sooner had it received a higher research and development priority. But in the meantime, Germany should have been more Soviet Union-like in its production of normal quality weapons. By that I mean it should have focused on a small number of designs, and those designs should have been as simple and as easily mass produced as possible.

Getting the right mixture of basic, advanced and super weapons (and other tools of war) is indeed a good recipe for victory (or at least for improving your chances of victory) – and, as you point out, it’s much easier to see the correct ingredients in retrospect. An example of this type of mixture was given by Eisenhower after the war when he listed what he considered to be the four things which won WWII for the Allies. One of them, the atom bomb, is clearly in the superweapon category. Another one, the bazooka, can be regarded as an enhanced conventional weapon: sophisticated and effective, but based on relatively straightforward principles (the Monroe effect) which had been known as far back as 1888, and which did not not require a huge effort like the Manhattan Project to produce a practical weapon. The other two, the jeep and the C-47 Skytrain / Dakota / Gooney Bird, were multi-purpose transportation devices – unromantic and harmless-looking, but immensely valuable as logistical support systems and as providers of battlefield mobility for ground forces and paratroops.

Bread-and-butter tools like transport vehicles and cargo planes aren’t as flashy as tanks and fighters, but they are vitally important. There’s a great scene towards the end of the 1949 movie Battleground which shows just how much these machines meant to the troops. The American forces surrounded at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge have spent the movie holding the line against the Germans. Heavy cloud cover has prevented their resupply all through the battle, and the U.S. troops have almost exhausted their resources. The sky suddenly begins to clear, and moments later the drone of airplanes is heard in the distance. The soldiers scan the sky suspiciously , then suddenly jump up and shout “C-47s!!!” The sky fills with parachutes, and crates loaded with ammunition belts and ration packs start landing all around the troops, who rush to open them. Even if someone watching the movie doesn’t know anything about the course of the Battle of the Bulge, he or she would understand right away that this scene is the great turning point of the battle, and that the guys in Bastogne are going to be saved.

-

@CWO:

Getting the right mixture of basic, advanced and super weapons (and other tools of war) is indeed a good recipe for victory (or at least for improving your chances of victory) – and, as you point out, it’s much easier to see the correct ingredients in retrospect. An example of this type of mixture was given by Eisenhower after the war when he listed what he considered to be the four things which won WWII for the Allies. One of them, the atom bomb, is clearly in the superweapon category. Another one, the bazooka, can be regarded as an enhanced conventional weapon: sophisticated and effective, but based on relatively straightforward principles (the Monroe effect) which had been known as far back as 1888, and which did not not require a huge effort like the Manhattan Project to produce a practical weapon. The other two, the jeep and the C-47 Skytrain / Dakota / Gooney Bird, were multi-purpose transportation devices – unromantic and harmless-looking, but immensely valuable as logistical support systems and as providers of battlefield mobility for ground forces and paratroops.

Bread-and-butter tools like transport vehicles and cargo planes aren’t as flashy as tanks and fighters, but they are vitally important. There’s a great scene towards the end of the 1949 movie Battleground which shows just how much these machines meant to the troops. The American forces surrounded at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge have spent the movie holding the line against the Germans. Heavy cloud cover has prevented their resupply all through the battle, and the U.S. troops have almost exhausted their resources. The sky suddenly begins to clear, and moments later the drone of airplanes is heard in the distance. The soldiers scan the sky suspiciously , then suddenly jump up and shout “C-47s!!!” The sky fills with parachutes, and crates loaded with ammunition belts and ration packs start landing all around the troops, who rush to open them. Even if someone watching the movie doesn’t know anything about the course of the Battle of the Bulge, he or she would understand right away that this scene is the great turning point of the battle, and that the guys in Bastogne are going to be saved.

Solid post, and I can’t find anything in it with which to disagree! :)

As you pointed out yourself, unglamorous vehicles such as jeeps, military trucks, and cargo transport planes were of critical importance to the war. That was clearly an area in which the Allies had a very powerful advantage over the Axis. During WWII, Canada produced more military trucks than all Axis nations combined.

There were several reasons for this. One was that Germany and Japan–especially Japan!–were not as far along in their industrialization efforts as were countries like the U.S. and Britain. That meant less military production overall. The other problem the Axis had is that jeeps, military trucks, and cargo transport planes are no more useful than scrap metal except to the extent you can fuel them. Japan, it will be recalled, went to war on the U.S. in the first place because the U.S. had imposed an oil embargo and Japan had little or no oil supply of its own. Germany also had almost no oil. Romania ran at an oil surplus–which helped–but not enough. During the years leading up to the war, Hitler had tried to address the problem of insufficient oil through synthetic oil production. A number of experts told him his goal of major synthetic oil production was economically impossible. But as Adam Tooze notes in The Wages of Destruction, those experts had severely underestimated “Hitler’s sheer bloody-mindedness.” Consequently, Germany received a major amount of oil from synthetic oil production by the start of the war.

But even adding in the Romanian oil, they barely had enough for their existing motorized vehicles. An Allied-like transportation and supply effort would have been impossible unless Germany could acquire large amounts of new oil. This was exactly why Hitler found it so important to take and hold Stalingrad–he wanted access to the Caucasus oil fields.

-

The other problem the Axis had is that jeeps, military trucks, and cargo transport planes are no more useful than scrap metal except to the extent you can fuel them.

Yes indeed. Patton expressed this idea well in 1944 in a message he sent to his superiors pleading to be given greater priority in the Allied allocation of fuel supplies: “My men can eat their belts, but my tanks need gas!”

Japan, it will be recalled, went to war on the U.S. in the first place because the U.S. had imposed an oil embargo and Japan had little or no oil supply of its own. Germany also had almost no oil. Romania ran at an oil surplus–which helped–but not enough. During the years leading up to the war, Hitler had tried to address the problem of insufficient oil through synthetic oil production. A number of experts told him his goal of major synthetic oil production was economically impossible. But as Adam Tooze notes in The Wages of Destruction, those experts had severely underestimated “Hitler’s sheer bloody-mindedness.” Consequently, Germany received a major amount of oil from synthetic oil production by the start of the war. But even adding in the Romanian oil, they barely had enough for their existing motorized vehicles. An Allied-like transportation and supply effort would have been impossible unless Germany could acquire large amounts of new oil. This was exactly why Hitler found it so important to take and hold Stalingrad–he wanted access to the Caucasus oil fields.

This ties in with what I was mentioning earlier about the importance of having a coherent plan for winning a war, regardless of the level of technology a country has. Oil was absolutely crucial to all the major combatant nations in WWII, and as you point out Germany and Japan both had a critical lack of natural supplies in this area. It was vital for both countries to view the improvement of their oil situation as a top strategic priority – and both countries flubbed it. Japan correctly decided to seize the Dutch East Indies to obtain oil, but gave completely inadequate attention to the problem of defending its tankers from enemy submarine attack on the long sea voyage to Japan. As for Germany, a far more sensible option for it in 1941 would have been to invade the Middle East rather than the USSR. Germany could have secured vast oil resources that way (and by the same token would have deprived Britain of those same supplies). It could at the same time have caught the British troops in Egypt between its Middle East invasion forces in the east and Rommel’s existing forces in the west. This could potentially have knocked Britain out of Egypt / North Africa entirely, and deprived Britain of the use of the Suez Canal, its gateway to India, the Far East, Australia and New Zealand.

-

@CWO:

Yes indeed. Patton expressed this idea well in 1944 in a message he sent to his superiors pleading to be given greater priority in the Allied allocation of fuel supplies: “My men can eat their belts, but my tanks need gas!”

I’m currently reading a book which makes the case Patton was assassinated by the U.S. government. The evidence for assassination is quite compelling, though not 100% conclusive. The book is worthwhile not just for information about the assassination attempt, but also because of the historical background information it presents. The WWII and early postwar administrations of FDR and Truman were pro-Soviet–so much so that if you suspected the Soviets, you became suspect yourself. Patton was strongly anti-Soviet, and therefore a source of friction in the alliance between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. that FDR in particular had hoped to build. Patton also protested the Morgenthau Plan and other acts of mass murder perpetrated by the Allied governments in the postwar era.

FDR also believed that the Soviet Union deserved to control most of postwar Europe because it had done the bulk of the work of defeating Germany. On the one hand Stalin had wanted a second front for Germany–which FDR provided on D-Day–but on the other he didn’t want the Western democracies to get too much of postwar Europe. FDR had no objection to this. The problem was that one of his generals was too good, and threatened to take too much of what both FDR and Stalin felt should be in the Soviet sphere. To prevent this from happening, Wilcox writes, Patton was deliberately and frequently deprived of the gas he needed to advance rapidly eastwards into Germany. That decision drew the war out and cost many lives. But on the bright side–at least from FDR’s and Stalin’s perspective–many, many more people lived under Soviet or Soviet satellite rule in the postwar era than would have been the case had Patton received his gasoline.

@CWO:

This ties in with what I was mentioning earlier about the importance of having a coherent plan for winning a war, regardless of the level of technology a country has. Oil was absolutely crucial to all the major combatant nations in WWII, and as you point out Germany and Japan both had a critical lack of natural supplies in this area. It was vital for both countries to view the improvement of their oil situation as a top strategic priority – and both countries flubbed it. Japan correctly decided to seize the Dutch East Indies to obtain oil, but gave completely inadequate attention to the problem of defending its tankers from enemy submarine attack on the long sea voyage to Japan. As for Germany, a far more sensible option for it in 1941 would have been to invade the Middle East rather than the USSR. Germany could have secured vast oil resources that way (and by the same token would have deprived Britain of those same supplies). It could at the same time have caught the British troops in Egypt between its Middle East invasion forces in the east and Rommel’s existing forces in the west. This could potentially have knocked Britain out of Egypt / North Africa entirely, and deprived Britain of the use of the Suez Canal, its gateway to India, the Far East, Australia and New Zealand.

You’ve made very strong points. The possibility of an invasion of the Middle East–most likely through Turkey–should have been very strongly considered. (I don’t think that Germany had the extra transports + naval strength necessary for a sea invasion of the Eastern Mediterranean.) Ideally, Turkey could be pressured to become part of the Axis on its own; thereby granting the German Army immediate access to the British lands beyond. But Germany could also have fought its way through the Turkish mountains if necessary. The problem with that option would have been the inherent delay, and the chance for Britain to build up its army’s strength through soldiers from its colonies. If an invasion of Turkey had been necessary, I would think that nearly two years would have been needed between the beginning of the invasion and its conclusion. (Presumably with one German force swinging south from Turkey to meet the other force pushing east from Libya.) Success on this front would have given Germany the oil you mentioned, while facing a much weaker land force than the Red Army.

There were several reasons why Germany did not do these things. The first is Hitler’s thought that war between Germany and the Soviet Union was inevitable. He was therefore leery of concentrating too much of Germany’s strength in some venture such as the above, leaving it vulnerable closer to home. That fear may or may not have had a basis in reality. Another, highly credible perspective on Soviet diplomacy is that Stalin regarded both fascists and democracies as equally enemies; and therefore wanted the two sides to fight each other in as long and bloody a war as possible while the Soviet Union stayed neutral. Then when both sides had been bled white, the Red Army would move in to pick up the pieces. There is, however, the chance Stalin would have made a move early, especially if Germany looked weak.

Another reason Hitler launched the war against the Soviet Union was because he didn’t want to give Stalin the time to complete his program of industrialization and militarization. However, that program was much further along than Hitler had realized. It was Germany, not the Soviet Union, that required extra time to catch up. A third factor which led Hitler to choose the Soviets as his next target was the fact the Red Army had seen its performance severely downgraded by purges–a fact which had become evident in the Winter War against Finland.

But perhaps the main factor which led to the decision to invade was the misperception of the strength of the Red Army. Prior to Barbarossa, German military planners had believed the Red Army consisted of 200 divisions. But by the fall of '41 it consisted of 600 divisions, and the Soviets had attained a recruitment level of 500,000 men a month: a level they would sustain for the bulk of the war. Instead of the relatively rapid, blitz-like conquest of the western Soviet Union–a conquest which would have obtained for Germany the oil and grain it desperately needed–Germany found itself itself in a long, grinding, brutal war against an enemy much larger and stronger than itself; with an army and weapon production capacity several times as large as expected. A plan is only as good as the information it’s based upon; and Germany’s plan for victory was based on very faulty information indeed.

-

Hmm, seems like a few have been watching too many History Channel specials on German technology, or basing too much info on achtungpanzer.com (which is known for not being the best source of info on German armor and other tech).

For instance, the OP’s article claims the Ak-47 was a direct copy of the Stg.44. While the design of the Stg. 44 undoubtedly had a bearing on how Kalashnikov would style his rifle (and all other assault rifles developed in the future), the internals of the two rifles couldn’t be much more dissimilar. The bolts and locking systems in the rifles are different, and though both use similar methods of working the action (gas-operated) neither rifle pioneered this system. Both are select fire but use completely different selector systems. I would say Kalashnikov probably copied the use of intermediate rifle rounds in the Stg.44 (7.92 kurz) for his rifle (7.62x39), but others suggest he could have gotten the idea from the .30 carbine used in the U.S. M1/M2 carbines.

While it may seem a trifle subject to debate, it is a good one in demonstrating that many of Nazi Germany’s “high-tech” weapons weren’t really that innovative and didn’t have the kind of bearing on the post-war world that many today believe.

Take Germany’s wartime rocket program. Despite almost endless funds into the V1/V2 missiles, these weapons were barely more than glorified bottle rockets and when they managed to hit their target, did little damage. Around 5,800 of these weapons were fired at Britain and some 500 of them actually hit, killing around 9,000 Britons. Compare this with the round-the-clock bombing by the Allies, which killed tens of thousands of Germans and severely damaged the country’s infrastructure, and you can’t help but see that the whole program was a waste of time - as some in this discussion have already mentioned.

The American Bombing Survey, studying Germany’s defense industry and research programs after the war, concluded that Germany could have built at least 24,000 extra planes with the resources dumped into the missile programs. In any case, when captured German scientists were taken to the U.S. to help develop its own rocket program, U.S. scientists quickly realized the Germans weren’t all that far ahead.

I’ve seen the Me-262 hyped up considerably on this forum. For one, the fuel consumption of the Schwalbe and other jets was beyond Germany’s ability to meet. Furthermore, while the Schwalbe could out race Allied prop-fighters for a period of time, it was no match for the maneuverability or endurance of the latest Allied planes, the Spitfire Mk IX+ and P-51s and Lavochkin-7s. Most damning, however, was the state of German pilot training from 1943 on. By the end of the war, young German pilots left flight school with just a few hundred hours of flight time and were easy prey for crack Allied pilots. Their skills were barely adequate to get a prop plane of the tarmac, let alone operate a Me-262.

Another example , the Pzkw. VI, or Tiger. While the Tiger’s gun could take out most Allied tanks beyond their own range, and its armor not easy to crack, the tank was a logician’s worst nightmare. Besides the outrageous fuel consumption, a Tiger had to have its engine replaced about every 100 miles or so (and, since the German war industry inexplicably failed to produce adequate numbers of spare parts for any of its machines, there were never enough engines to go around). The Tiger’s interleaved suspension system, which gave the best ride of any tank of WWII, proved to be more of a liability than an asset on the Eastern front, where mud and water froze in between the outer and inner road wheels and prevented the tank from moving. The Russian T34 and U.S. Sherman were much better amalgamations of those three basic, but interdependent, characteristics of armor development: mobility, armor and firepower. The Tiger and other German heavy tanks were barely more than semi-mobile pillboxes.

The list really goes on and on. As one poster mentioned below, inadequate sources for fuel drove Germany to develop synthetic fuels. By the middle of the war, Germany was getting about three quarters of its fuel from synthetic sources, including from acorns and grapes in captured French vineyards. This fuel increased Germany’s ability to stay in the war (oil was their Achille’s Heel) but much of it was developed from low-grade lignite and other sources mentioned above, so the quality was subpar at best. It took German pilots far too long to realize their 87-octane fuel was no match for the pure aviation fuel used in U.S. and British planes, which gave Allied aircraft sudden bursts of power and overall much better performance.

I’m not saying Germany didn’t produce high tech weapon systems, but none (besides a German a-bomb) nor any combination of those wonder weapons could have had any major impact against the Allied steamroller to victory. The one German device that could have possibly changed the war’s outcome, the submarine snorkel, was developed by a Dutchman.

Now, take some Allied innovations that actually had a tangible, incredibly decisive effect on the war, like ASDIC and sonar, cavity magnetrons and radar, Liberty ships, convoy systems, Ultra, the atomic bomb, B-29 strategic bomber, and the list keeps going, all the way down to the superior infantry weapons used by Allied (especially American) soldiers.

The most important Allied innovation, however, was the American and Russian systems of mass production. Hitler and many German industry planners eschewed mass production, and felt every piece of equipment should be handmade - a piece of art, one of a kind and with all the latest features. Speer turned much of this around, but it was far too late to save Germany. Germany understood far too late the kind of industry total war requires, and this is arguably the country’s biggest war time mistake.

Richard Overy put it best in “Why the Allies Won”:

“The war accelerated the technical threshold, and brought the weapons of the Cold War within reach, but no state, even the most richly endowed, was able to achieve a radical transformation of military technology before 1945. The war was won with tanks, aircraft, artillery and submarines, the weapons with which it was begun.”Edit: Sorry for the extremely long post. This is a controversial issue and one that’s always fun to argue over! If you are seriously interested in what made the German military in World War II so impressive, at least during the early part of the war, you have to look into German innovations that are less glamorous than Fritz flying bombs,“stealth bombers” and curved barrels (shakes head): military training in which NCOs and junior officers were taught to take the initiative and make their own tactical decisions; a superb doctrine of combined arms; and simple radios which, when provided to platoon leaders, tanks and aircraft, allowed unprecedented communication and coordination between different assets on the field. These are the innovations that made the German military so successful in the early years (these and the fact that Germany choose to fight Continental countries which were much weaker than itself, that is, until Barbarossa).

-

The Me 262 achieved a 5:1 kill ratio, and I don’t see why the (very fast) Horten flying wing couldn’t have done the same.

Could you provide a source for these figures? Almost everything I’ve read states the Schwalbe as having a pretty poor loss/kill ratio. JG44 and some other small, elite units may have reached a ratio of maybe more than 1:2, but on the whole, the jet was too plagued with problems, too short of spare parts, too wasteful in fuel and piloted by too many inexperienced fliers to have had the kind of history you say. Approximately a hundred Allied planes were shot down by Me-262. Compare that figure to the 1,400 or so Me-262s that actually reached an airfield, you’ll see the jet’s history wasn’t so impressive, with a kill/produced ratio of approximately 1:14. Given time, the Me-262 could have had a larger impact, but remember, German military technology wasn’t created in a vacuum. The Allies were taking notes and had their own designs in the work. They had the scientists and the industry to surpass in quality and quantity anything the Germans could put up. Besides, what good are jet aircraft when your soldiers holding the front line are running out of ammunition and food, or when your infrastructureis being bombed day and night?

And the Horten, well, it would have crashed just as easily as any of Germany’s other rushed, untested and largely ineffective wonder planes, whether at the guns of an Allied pilot or by accident. :wink:

-

Could you provide a source for these figures? Almost everything I’ve read states the Schwalbe as having a pretty poor loss/kill ratio. JG44 and some other small, elite units may have reached a ratio of maybe more than 1:2, but on the whole, the jet was too plagued with problems, too short of spare parts, too wasteful in fuel and piloted by too many inexperienced fliers to have had the kind of history you say. Approximately a hundred Allied planes were shot down by Me-262. Compare that figure to the 1,400 or so Me-262s that actually reached an airfield, you’ll see the jet’s history wasn’t so impressive, with a kill/produced ratio of approximately 1:14. Given time, the Me-262 could have had a larger impact, but remember, German military technology wasn’t created in a vacuum. The Allies were taking notes and had their own designs in the work. They had the scientists and the industry to surpass in quality and quantity anything the Germans could put up. Besides, what good are jet aircraft when your soldiers holding the front line are running out of ammunition and food, or when your infrastructureis being bombed day and night?

And the Horten, well, it would have crashed just as easily as any of Germany’s other rushed, untested and largely ineffective wonder planes, whether at the guns of an Allied pilot or by accident. :wink:

Thanks for the long posts. It’s always good when someone contributes something well thought-out to the discussion.

My source for the 5:1 kill ratio of Me 262 jets is here. I’ve read that the ratio increased to 10:1 when the jets were equipped with the latest air-to-air missiles (though that ratio is based on a relatively small number of combat missions).

Compared with Allied fighters of its day, including the jet-powered Gloster Meteor, [the Me 262] was much faster and better armed.[6] . . . Luftwaffe test pilot and flight instructor Hans Fey stated, “The 262 will turn much better at high than at slow speeds, and due to its clean design, will keep its speed in tight turns much longer than conventional type aircraft.”[34] . . . Allied pilots soon found the only reliable way of dealing with the jets, as with the even faster Me 163 Komet rocket fighters, was to attack them on the ground and during takeoff or landing.

Several times you mentioned Germany’s oil-related problems. (Its lack of fuel for its jets, the low octane of its fuel, etc.) The small amount of training its pilots received toward the end of the war was likewise a consequence of its lack of fuel. (The fuel shortage prevented them from receiving adequate training time.)

The fact that Germany lacked the same natural resources as its enemies (or indeed enough natural resources to sustain a first-rate war effort) does not mean that the designs arrived at by its engineers were flawed or second-rate.

It is true that jets were less maneuverable than most piston-driven aircraft. In general, the slower an aircraft, the smaller its turn radius. That is for the same reason that your car has a smaller turn radius when going 10 MPH than when it’s going 80 MPH. Whenever you manage to increase an aircraft’s speed you’ll generally lose some maneuverability. Despite that trade-off, faster aircraft were generally superior to slower aircraft (all else being equal). Jets were no exception to that rule.

I agree that Germany’s V2 rockets had little or no military value. (Beyond the effect of distracting Allied bombers from other, more useful targets.) But I disagree with the assertion that the German rocket program wasn’t far ahead of the Americans’ program. During the initial postwar era, the American rocket program faltered, largely because the captured German rocket scientists were viewed with distrust. America tried to make do without allowing the German rocket scientists to contribute much, if anything, to the U.S. rocket program. As the Soviets began making significant progress of their own, and as some of the distrust toward the German scientists began to fade, the German scientists were allowed to do more. Their efforts resulted in the U.S. getting back in the lead. Werner von Braun was in charge of designing the Saturn V rockets that put men on the moon. He based those designs on the Aggregate rocket series he and his team had been working on back in Germany.

You have correctly pointed out some of the flaws associated with the Tiger tank. But I feel you’ve overstated the case. In any case, Germany was in the process of creating replacement tank designs that were more powerful than its existing tanks, while also being much more easily mass-produced and far more mechanically simple and reliable.

Germany’s innovations in submarines went far beyond just the schnorkel (which as you point out, was invented by the Dutch). Its type-XXI U-boats had a hydrodynamic design, a sophisticated electronics suite, highly extended battery life, and other advanced innovations. Either those or similar subs had a radar-aborbant rubber coating to make them harder to detect. Germany’s late-war submarines had far more in common with the nuclear subs of the postwar era than with contemporary WWII subs.

Likewise, the Panzerfaust handheld anti-tank weapon was among the best infantry weapons of the war. Germany had been progressively upgrading its range, with plans in the works to continue the range upgrades.

You mentioned several Allied inventions. While some of them–such as the nuclear bomb–are indeed impressive, others are not. For example, the idea of ship convoys is hardly a stroke of technological genius. Back in the dinosaur age, brontosaurs had used a similar concept to allow the adults to protect the young from predators. Other Allied innovations–such as radar, sonar, and so on–were also employed by the Germans. (It is also worth noting that the Japanese had contributed extensively to pre-war radar research efforts; but that the Japanese military did not initially believe that research could be converted into militarily useful applications. Therefore, Japanese radar development lagged a few years behind the U.S., Britain, and Germany.)

The Allies were able to produce weapons in much larger quantities than were the Axis. Partly this was because all three major Allied nations were several years ahead of Germany and (especially!) Japan in implementing mass production techniques. It was also because the Allies had access to far more manpower and raw materials than did the Axis. As a result of this resource differential, anything new or innovative the Allies deployed could be released in very large numbers, and in a way that would have a massive impact on the course of the war. In contrast, the Axis’s limited resources and deteriorating war situation meant that whatever new designs they released would tend to fall into the category of “too little, too late.” But the fact that the Axis lacked the resources to produce large numbers of the weapons its engineers designed does not in any way detract from what those engineers had achieved!

To give an example of this, Germany invented the first stealth bomber. This aircraft implied a much deeper understanding of aviation than did the Allies’ aircraft designs. (The same could also be said about Germany’s fighter jets.) But the war ended before this aircraft could be mass-produced. Conversely, the construction of large, four-engined planes (such as the ones the Allies created) did not necessarily represent a radical leap forward. Such planes were remarkable mostly because the Allies had the industrial capacity to produce enough of them to matter. The blueprints for the Superfortress would have been useless to the Axis because they lacked the excess industrial capacity required to produce significant numbers of those planes. (It is much, much easier to build a single-engined aircraft than a four-engined Superfortress.) In contrast, the blueprints for the late-war German innovations (type XXI U-boats, Me 262, stealth bomber, assault rifle, Panzerfaust, air-to-air missiles, Wasserfall surface-to-air missiles, infrared vision equipment for tanks, etc.) would not have been useless to the Allies. On the whole, Germany had significantly better and more advanced late-war weapons designs than the Allies. But the Allies were much better-positioned to take advantage of any given weapon design.

-

My source for the 5:1 kill ratio of Me 262 jets is here. I’ve read that the ratio increased to 10:1 when the jets were equipped with the latest air-to-air missiles (though that ratio is based on a relatively small number of combat missions).

Compared with Allied fighters of its day, including the jet-powered Gloster Meteor, [the Me 262] was much faster and better armed.[6] . . . Luftwaffe test pilot and flight instructor Hans Fey stated, “The 262 will turn much better at high than at slow speeds, and due to its clean design, will keep its speed in tight turns much longer than conventional type aircraft.”[34] . . . Allied pilots soon found the only reliable way of dealing with the jets, as with the even faster Me 163 Komet rocket fighters, was to attack them on the ground and during takeoff or landing.

The kill/loss ratio in the Wiki article is referenced to William Green’s “Warplanes of the Third Reich,” a fantastic and exhaustive compendium on German aircraft of WWII. I have a copy at home but I’ve always been skeptical of many of the figures he quotes in the chapters dealing with Germany’s jets. He hypes up the effectiveness of the Me-262 without going into much detail on whether these figures describe certain Schwalbe units (like JG/7 or JG/44) or the entire Me-262 fleet.

Some units were able to achieve disproportionate results with the Schwalbe, but these squadrons (such as Galland’s) were comprised of the Luftwaffe’s best surviving pilots. Every loss (and they suffered many - both in combat and accidental) meant a drastic decrease in the unit’s effectiveness, and considering the attrition rate for German pilots starting 1943, there was little hope of receiving any well-trained replacements.

Also, I don’t know how much faith I would but in Hans Fey’s quote, considering he was a Luftwaffe instructor and has a bit of a bias. Imagine being a Me-262 instructor in 1944 Nazi Germany. The classroom is filled with young (including some Hitler Youth) men, many still boys, most of whom had only ever seen a plane, let alone flown one.

The war is closing in on Germany from all sides and any thoughts of victory are deluded. The Luftwaffe has just begun receiving sizable numbers of operational Me-262s and you’ve been put in charge of training a squadron of jet pilots. You’ve seen the decimation of Germany’s air force, its complete impotency against the Allied bomber fleets and the superior Allied fighters. You’ve trained countless men, excellent fliers, only to see them again on a casualty list.

Now, you see the scared looks on the faces of all the flight students. Air sirens whine in the distance, signaling another bomber raid and swarms of escort fighters looking for easy targets. You look around the room and see the nervous faces of each of those young men, most of whom, you know without a doubt, will die without ever shooting down an enemy plane.

What do you tell your flight students?In any case, you say the Me-262 was faster and better armed than its UK equivalent. Both are true, but does it really make the Schwalbe superior? For one, as the Wikipedia article mentions, the Schwalbe’s speed (the only feature that kept more from being shot down by Allied fighters) made target acquisition difficult at best, if not impossible for the less experienced fliers. This drawback, and the Me-262’s habit of burning out its engines when the throttle was hit too fast (a problem never fully solved during the war, and one that was fairly common especially if you noticed a pair of Mustangs behind you) negates much of the speed advantage.

Now, the Mk 108 cannons. Powerful, yes, but totally inadequate for air-to-air combat. The short-recoil-operated weapon, with its short barrel and low muzzle velocity, made it a vary inaccurate weapon for air-to-air combat. Large aircraft like B-17s could be hit with a degree of accuracy, but Schwalbe fliers had to use the utmost discipline to prevent running out of ammunition when engaging Allied fighters. If I remember right, the Mk 108 was highly prone to jamming, especially under the stress put on it during high speed air combat.

The Meteor, on the other hand, was armed with four HS.404 20mm cannons, proven, tried and trusted air-to-air weapons that were the standard for most automatic cannons fitted on US/UK planes. While the 20mm lacked the punch of the 30mm Mk 108, it far surpassed the German gun in muzzle velocity (840m/s to 540m/s) which meant it was more accurate and could reach the target faster. The weight of fire (that is, the weight of all the projectiles fired in a given period of time) was pretty similar between the two planes.Here is a great article (with accompanying discussions) compiled by the many experts over at the Tanks in World War II forum that highlights these and other deficiencies suffered by the Schwalbe:

http://www.weaponsofwwii.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=44

Whenever you manage to increase an aircraft’s speed you’ll generally lose some maneuverability. Despite that trade-off, faster aircraft were generally superior to slower aircraft (all else being equal). Jets were no exception to that rule.

You are right, with all else being equal. But, by the time the Me-262 entered service, there was nothing equal between the German and Allied air forces. Also, Allied pilots didn’t just give up every time they encountered a Me-262. They and their commanders developed tactics against the Schwalbe that obviously worked and largely neutralized the threat the jet posed. Again, the Schwalbe was not produced and operated in a vacuum. You can’t judge its efficiency by taking it out of the context in which it was developed and fielded. Just because the Me-262 should have been superior doesn’t mean it actually was.

You have correctly pointed out some of the flaws associated with the Tiger tank. But I feel you’ve overstated the case. In any case, Germany was in the process of creating replacement tank designs that were more powerful than its existing tanks, while also being much more easily mass-produced and far more mechanically simple and reliable.

To be honest, I thought I was going easy on the Tiger! Anyways, the “E” series of tanks were never anything more than than paper projects (besides that, no process to create these tanks ever began). They don’t really testify to the superiority of German tank design either, as the Allies were already producing simple, reliable and highly effective tanks. With the E series, German planners were again failing to realize the efficiency of a few reliable models. Why produce five for six models, as the E series called for, when the U.S. and USSR were able to do fine with just one apiece (ok, the Soviets armored divisions still relied on KV tanks in many battles, but these were largely mothballed when the T34/85 appeared)? In any case, those tanks would have done nothing more for Germany than add a few extra targets for circling Sturmoviks and P-47s.

You mentioned several Allied inventions. While some of them–such as the nuclear bomb–are indeed impressive, others are not. For example, the idea of ship convoys is hardly a stroke of technological genius. Back in the dinosaur age, brontosaurs had used a similar concept to allow the adults to protect the young from predators. Other Allied innovations–such as radar, sonar, and so on–were also employed by the Germans.

Those innovations may not have been impressive, but that does not take away from their decisive nature during the war. Convoys drastically reduced the u-boat menace by providing large groups of merchant ships with escorts (from frigates, destroyers, carriers and other escorts) and defense in numbers. The people of England, who feared the loss of their supply lines, sure thought the convoy system was impressive.

And yes, Germany fielded radar and sonar systems, but that’s not the point I was making. These were Allied innovations and though the Axis fielded similar systems, they were never as advanced as what the Western Allies possessed. By the middle of the war, Allied radar was advanced enough for a patrolling plane to detect the surfaced periscope of a German submarine from quite a distance away.I believe you may have explained why Germany (in at least my opinion) receives too much undeserved credit for its “technological superiority”: Germany, in her sheer desperation, researched dozens and dozens of supposedly “war-winning” weapons and in the process created the prototypes for some pretty cool looking hardware. Allied innovations, which in my opinion were much more superior and effective than anything Germany produced or had near production, are often glossed over because they aren’t as cool looking as Schwalbes, Pzkw. VIIIs or Fritz flying bombs. Sonar and radar (as well as many other innovations like Ultra) aren’t terribly awesome looking devices, but again and again they allowed the Allies to out smart, out maneuver and out fight their enemies, and in the end, that’s all that mattered. This is part of human nature’s insistence on rooting for the underdog, I suppose; the Allies won, so who cares how they did it? Now, the Germans lost, but they developed some cool looking hardware along the way. If only they had more of it, they would have won, right?

So, let me submit to you one Allied innovation that not only had a decisive effect on the war, but was one mean, badass piece of machinery: the U.S. Essex-class CV (I would mention the Midway-class as well, but it was commissioned in the closing months of the war and, IIRC, never saw any action in WWII, though the class survived until its last carrier was decommissioned in 1992 (which, considering the class’ longevity, testifies to the level of technological superiority the U.S. had reached by 1945).

I’d like to debate a few more items with you right now, but my wife tells me its too beautiful outside to sit at the computer all day!

-

The kill/loss ratio in the Wiki article is referenced to William Green’s “Warplanes of the Third Reich,” a fantastic and exhaustive compendium on German aircraft of WWII. I have a copy at home but I’ve always been skeptical of many of the figures he quotes in the chapters dealing with Germany’s jets. He hypes up the effectiveness of the Me-262 without going into much detail on whether these figures describe certain Schwalbe units (like JG/7 or JG/44) or the entire Me-262 fleet.

I did a little digging, and found another source which cites a 4:1 kill ratio for the Me 262. Every source I’ve seen has cited a kill ratio in the 4:1 - 5:1 range.

You mentioned that the Me 262’s fast closing speed was a disadvantage, in that there was little time to fire at enemy aircraft before the jet overtook them. However, a tactic was designed to counter that problem. The jet would first fly above the bomber formation, then would swoop below, and finally would pull up to the bombers’ level. That last maneuver would reduce the jet’s closing speed to allow more time to fire. Later, the problem of attacking bombers was considerably simplified when the jets were given R4M rockets (which had a much longer attack range than the 30mm cannon).

Also, I don’t know how much faith I would but in Hans Fey’s quote, considering he was a Luftwaffe instructor and has a bit of a bias.

That’s possible. On the other hand, an instructor’s primary objective should be to keep his students alive. You don’t achieve that by feeding them false information. In any case, the statements Fey made in that quote are confirmed by the following NASA website. In addition to confirming Fey’s statements about the Me 262’s turning characteristics, the NASA website indicated that, “The Me 262 seems to have been a carefully designed aircraft in which great attention was given to the details of aerodynamic design. Such attention frequently spells the difference between a great aircraft and a mediocre one.”

Why produce five for six models, as the E series called for, when the U.S.

and USSR were able to do fine with just one apiece (ok, the Soviets armored

divisions still relied on KV tanks in many battles, but these were largely

mothballed when the T34/85 appeared)?It is incorrect to assert the U.S. had just one tank model. In 1944, the U.S. produced four light tank designs, three medium tank designs, and one heavy tank design. The plan with the German E-series had been to have one tank design per weight category. For example, the E-5 (the smallest of the E-series vehicles) was to be 5 tons in weight and serve as the basis for things like armored personnel carriers, reconnoissance vehicles, light tanks, and so forth. The vast bulk of Germany’s tank production would likely have been E-50 Standardpanzers and E-75 Standardpanzers.

I believe you may have explained why Germany (in at least my opinion) receives too much undeserved credit for its “technological superiority”: Germany, in her sheer desperation, researched dozens and dozens of supposedly “war-winning” weapons and in the process created the prototypes for some pretty cool looking hardware. Allied innovations, which in my opinion were much more superior and effective than anything Germany produced or had near production, are often glossed over because they aren’t as cool looking as Schwalbes, Pzkw. VIIIs or Fritz flying bombs.

My view of the situation is different. The Axis was generally at a severe (2:1 - 4:1) disadvantage in terms of both military production capacity and manpower available for infantry. That numerical inferiority was why the Axis lost the war.

But the fact that the Axis war effort had been doomed by the Allies’ sheer quantity doesn’t mean we shouldn’t respect the technological innovations which occurred. One good measure of a technology’s worth is the extent to which it became the basis for postwar weapons or other innovations. Using that as the basis, the Allies made good technological progress during the war.

You mentioned the Essex class carrier as an Allied innovation. I’ll grant it was better than the German carrier under construction, or the Japanese carriers of the war. But how much of the superiority of the Americans’ design was the result of the fact that the U.S. could afford larger, more expensive, better carriers than could the Axis? In addition to the Essex carrier class, the Allies achieved innovations such as the following:

Wartime nuclear bomb–> postwar nuclear arms race

Wartime radar + sonar developments --> further developments postwar

Wartime computer technology --> postwar computer technologyIt is worth noting here that the Axis, and especially Germany, achieved progress in all three of the above-mentioned areas. In addition, Germany achieved the below list of developments–developments which were significantly ahead of their time.

Wartime jets + axial flow jet engines --> postwar axial flow jet fighters.

Wartime advanced jet designs (Me 262 HG III) --> postwar efforts to break the sound barrier

Wartime stealth bomber design --> 1980s era B2 stealth bomber

Wartime type XXI U-boats --> postwar nuclear submarines

Wartime air-to-air missiles --> postwar air-mounted weaponry

Wartime guided air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles --> postwar guided missiles

Wartime cruise missile (V1) --> postwar cruise missiles

Wartime V2 rocket --> postwar ICBMs

Wartime assault rifle --> postwar assault rifles

Wartime infrared vision equipment for tanks --> postwar night vision equipment

Wartime handheld anti-tank weaponry (Panzerfaust) --> postwar handheld anti-tank weaponry

Wartime Fritz guided bombs --> postwar smart bombs

Wartime Wasserfall surface-to-air missiles --> postwar SAMsIt is true that the Allies had made progress in some of the above areas. For example, the British had developed centrifugal flow jet engines (which are easier to design, but inferior to, the axial flow jet engines the Germans had designed). Nevertheless, the above list represents areas in which the Allies had either made no progress at all, or else were significantly behind the Germans. People are impressed with the late-war German research and weapons development not just because the weapons “looked cool,” but because it was clear that late-war Germany was in the midst of building a solid qualitative advantage over its enemies even as it was in the process of being destroyed. That is an impressive feat on a number of levels, especially considering the Allies’ advantage in population size and available funding.

-

But the fact that the Axis war effort had been doomed by the Allies’ sheer quantity doesn’t mean we shouldn’t respect the technological innovations which occurred. One good measure of a technology’s worth is the extent to which it became the basis for postwar weapons or other innovations. Using that as the basis, the Allies made good technological progress during the war.

You make a good point here, but the influence of Germany’s weapons on the post-war era is easily and often overstated, IMO.

Later, the problem of attacking bombers was considerably simplified when the jets were given R4M rockets (which had a much longer attack range than the 30mm cannon).

Practically useless against the opposing fighter planes of the time. Without knocking down the escorts, Germany was unable to even slightly weaken the Allied bombing campaign during the last years of the war. Perhaps the biggest aircraft-related RMA of WWII was that bombers by themselves do not win wars - they need escorts, and lots of them - and that escorts, with their ability to suppress enemy planes and other air defenses, were the true kings of the sky. But the reverse is also true - to attack the enemy’s bombing potential, you have to destroy his ability to escort those fighters. The Me-262 completely missed the mark as far as this military truism is concerned. With no ability to counter Allied escort fighters, the Luftwaffe was destined to lose the bomber campaign and any sliver of air superiority.

You mentioned the Essex class carrier as an Allied innovation. I’ll grant it was better than the German carrier under construction, or the Japanese carriers of the war. But how much of the superiority of the Americans’ design was the result of the fact that the U.S. could afford larger, more expensive, better carriers than could the Axis?

Well, if you grant this concession, you’ll be joining everyone else who knows anything about naval warfare in WWII. The German carrier, which if you’ll remember was never even completed, would have been a poor rival to the Essex and British Illustrious/Implacable classes, or for that matter, the Shokakus. Its aircraft complement would have been less than half of a fully loaded Essex, and in any case, what carrier-based fighters did Germany produce to compete against the Hellcats, Corsairs, and latest Seafires? The cruiser-caliber guns that would have armed the Graf and the associated role the Kriegsmarine envisaged for this carrier meant it probably would have ended up on the bottom of the ocean before too long.

Sure, the Essex was only made possible by America’s wealth in resources and labor, but you dismiss the technological feats apparent in the class’ design. With a speed of 30+ knots, the Essex could outrun almost any other warship. The C4ISR capabilities of this carrier were superior to any other combat ship of the war and set the way in design and tactics for future development of the U.S. Navy. The class survived until the early 1990s, testifying to the technological superiority and far-sightedness enjoyed by the U.S. during WWII (I apologize if far-sightedness is not a word, I couldn’t think of anything else!). The Essex is much more than a giant hunk of steel. It embodies the success of American society in producing and fielding the weapons that would win the war, from its able workforce and skilled designers to its first-rate scientists and to the competent sailors and fliers who were graduating from the world’s best military schools.

People are impressed with the late-war German research and weapons development not just because the weapons “looked cool,” but because it was clear that late-war Germany was in the midst of building a solid qualitative advantage over its enemies even as it was in the process of being destroyed. That is an impressive feat on a number of levels, especially considering the Allies’ advantage in population size and available funding.

It is wrong to assert that Germany had built any “solid” qualitative lead over the Allies. There were pockets of modernization but they were small and few between. By 1944 - the year in which Germany’s production capacity peaked - only one-tenth of the German army was mechanized. The rest were dependent on horses or by train, and were forced to fight a slightly refined version of the artillery and infantry battles of 1918. Germany’s efforts to introduce a new generation of aircraft (greatly stalled by Udet’s insistence that all aircraft - even four-engined planes - possess a dive-bombing capability) ended in a wasteful series of technical flops. The Luftwaffe was stuck throughout the war with proven but older planes. Allied planes only increased in sophistication and efficiency. I remember reading a famous order to German pilots to avoid any combat with the Russian Yak-3 because the Luftwaffe’s aircraft just couldn’t compete.

Germany developed some very sophisticated weapon systems (many of which were paralleled, though maybe not matched, by Allied research) but almost all were still in a stage of utmost infancy, despite tremendous allocations of resources and production. Many were second-rate and only marginally better than the systems they replaced, and in some cases were worse. The only reason many of these projects are even discussed is because they were thrown into combat, unfinished and untried, in a desperate attempt to clear the darkening clouds. Some German units were able to exploit the new systems to deadly use, but in most cases, the weapons were too underdeveloped to have any effect on the battlefield.

What is impressive to me is, during the second half of the war, how effective German soldiers could fight without support aircraft, short supplies, long marches on foot, a shortage of tanks and trucks, little ammunition and an enemy that only grew stronger.

-

. In addition, Germany achieved the below list of developments–developments which were significantly ahead of their time.

Wartime jets + axial flow jet engines --> postwar axial flow jet fighters.

Wartime advanced jet designs (Me 262 HG III) --> postwar efforts to break the sound barrier

Wartime stealth bomber design --> 1980s era B2 stealth bomber

Wartime type XXI U-boats --> postwar nuclear submarines

Wartime air-to-air missiles --> postwar air-mounted weaponry

Wartime guided air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles --> postwar guided missiles

Wartime cruise missile (V1) --> postwar cruise missiles

Wartime V2 rocket --> postwar ICBMs

Wartime assault rifle --> postwar assault rifles

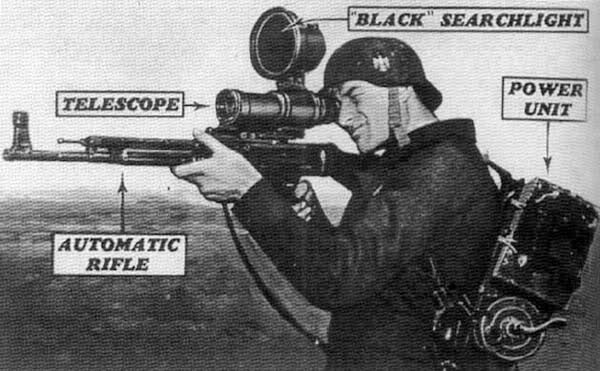

Wartime infrared vision equipment for tanks --> postwar night vision equipment

Wartime handheld anti-tank weaponry (Panzerfaust) --> postwar handheld anti-tank weaponry

Wartime Fritz guided bombs --> postwar smart bombs